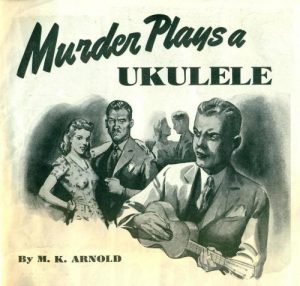

At some point or another, most of us in the ukulele community have seen this picture:

It is the illustration that accompanied the article Murder Plays A Ukulele by M.K. Arnold, published in the July 1941 issue of Master Detective Magazine. Subtitled, “A ukulele – an abandoned car – and a bicycle on the beach . . . smart detective work linked them together and nabbed the killer.” The picture itself is more than a bit off, as the two main characters were only a couple years different in age, both in their early 20’s, and both played the ukulele.

This isn’t a work of fiction, it is a true story! But it took my librarian sister, Sarah Howard, almost a year to unearth a copy of the article in the Library of Congress and get it to me.

Frederick David Galloway was born in New York in 1902 and lived an idyllic childhood. He was discovered to be a vocal prodigy and quickly became known for his soprano voice, giving concerts at the local church and even appearing at the Educators’ Conference. His father, Emil R. Galloway, was a former Congregational minister who later worked as the editor of the Santa Cruz Weekly Herald. The younger Galloway grew up performing in vaudeville in New York, singing and dancing — and playing the ukulele. He continued playing throughout his life.

When he turned 15, he lied about his age and joined the Army. He was soon sent to an overseas field hospital in France during World War I. Upon returning to the states, he then spent nine months at a federal prison in Georgia for driving a stolen car into another state. Despite his record, he re-enlisted in the Army, but only lasted about six months before he deserted. Throughout his time in service he continued to perform at clubs and vaudeville venues with his voice and ukulele.

In 1926 he found himself in San Jose, California, busking at the Rose Fiesta there and encountered another ukulele player, Andrew Pashuta. The two of them recognized their mutual love of the ukulele and combined forces. Andrew even put Fred up in his boarding house room. Pashuta had his landlady come up and hear Andrew play, saying, “He can make it talk.”

For three nights starting on Thursday, the two of them played together and collected money from the crowds. They were able to buy some white liquor, prohibition still being in full force. When the crowd at the park slowed down on Saturday, they decided to head to another club in the area, Chuck Leddy’s, hoping to get a gig. They hopped in Andy’s Chevy roadster and headed out. It was early, so they stopped along the road to drink and swap stories. During their gab session Fred revealed that he had served time in a federal prison for stealing a car and crossing state lines and was currently an Army deserter.

Pashuta threatened to expose Galloway as a deserter and an ex-con. Fearing the exposure, Galloway said in his drunken stupor he grabbed the first thing available and hit Pashuta. What he grabbed was the starter handle for the motor and the autopsy revealed that Andy had been hit four times, two of them being particularly brutal. Galloway than dragged the body to a field about 75 feet away and covered it with some handfuls of grass. He than drove the car back to the boarding house, packed up his clothes and some of Pashuta’s and headed out. He drove the car to Salinas where the car broke down. After leaving the car with a farmer he hitchhiked south to Venice Beach.

Based on the descriptions the police were able to obtain from the landlady and some folks from the park, a postcard size description was printed up and passed to other law enforcement offices in nearby communities along with the added note that the suspect might have two ukuleles.

For two weeks Galloway sang and danced along the boardwalk at Venice Beach, using the alias Fred Rowland. Two local officers had encountered ‘Rowland’ when a young boy said a man had dumped his bicycle out in the water where he couldn’t get it. The officers made Galloway retrieve the bicycle and warned him to behave. A few hours later, having found the postcards left by the San Jose detectives, they realized that it might very well be describing the man they had chased off the beach earlier.

They returned to the area and eventually found the individual through a couple of recent encounters he had with other law enforcement officers. He also had attacked a taxi driver when refusing to pay his fare. When confronted in his apartment by the officers, he provided his correct name. There were also two ukuleles on the table. They took him to station and booked him on suspicion of murder. Hearing the charge, Galloway wilted and pretty much confessed to the events.

On the drive back to San Jose, he entertained the two police officers by singing and playing “The Prisoners Song” on his victim’s ukulele.

Now if I had the wings like an angel

Over these prison walls I would fly

And I’d fly to the arms of my poor darling

And there I’d be willing to die.

“The Prisoner’s Song” is a 1924 song by Vernon Dalhart (1883-1948). It was a hit, and many say it was one of the greatest songs of the 1920s decade. It has been re-recorded by many famous artists such as Hank Snow, Johnny Cash, and Bill Monroe.

Galloway was quickly found guilty of the murder and was sentenced to death. But his case was retried after a judge learned that a juror had said she would vote to hang any man who was a “drunkard.” Upon appeal, the California Supreme Court determined that the jury had been tainted by this individual and ordered a retrial. After the second trial, Galloway was sentenced to life in prison.

While in prison, Galloway started a prison newspaper, predominantly focused on sports. Greatly enjoyed by the inmates, the paper expanded and was well received by the journalism community outside the prison and garnered a couple of awards. In the years he was there, he met many famous sports figures that came to the prison for demonstrations and exhibitions. Among them were Wimbledon champion Bobby Riggs and future Wimbledon winner Jack Kramer. Right-handed Riggs played left-handed and beat everyone, including Galloway. On Feb. 2, 1941, major league baseball players, from such teams as the New York Yankees and Boston Red Sox, showed up to play an exhibition game. In the stands were two world heavyweight boxing champions — Max Baer and the “Great White Hope,” Jess Willard.

After serving a little over twelve years in prison, Galloway was released. He joined a couple of other ex-convicts and committed a string of robberies that resulted in his being returned to Folsom Prison for violation of parole. Once there, he continued to work on the newspaper.

Galloway was finally released in 1959. “Hank” Osborne, city editor of the now-defunct Mirror, sent a reporter to write about Galloway’s first days of freedom. But the reporter found more than a story, and told his editor so.

“Hank, I don’t want to write this story. I want you to give this guy a job on the paper,” said former Mirror and Times reporter Paul Weeks. Osborne did just that, and Weeks waited two decades to write Galloway’s story. Galloway worked at the Mirror, then at The Times, until he retired in 1973. He died in 1987.

The information in this article is based:

Arnold, M.K., Murder Plays A Ukulele, July 1941, Master Detective Magazine

People v. Galloway, 259 P. 332 (Cal. 1927), Appeal of the original conviction/sentence

Rasmussen, Cecilia, Convict Took Up the Pen While Serving in One, Jan 11, 2004, LA Times